15 x 15

The works are created from a framework constituted by triangular base patterns, but executed through diverse materials like industrial ceramics, paper, charcoal, and paint. It is partly about developing networks and rhythms in which line and color play a structuring role to generate images where geometry, projection, and symmetry unfold as the fundamental resources of the "visual grammar" of the work. Additionally, it aims to juxtapose this mode of work, firmly anchored in the tradition of hard-edge abstract painting, with a ceramic sculpture whose qualities point towards its opposite, a repertoire of works whose formal characteristics refer to biological, plant, or animal bodies, but paradoxically embodied in clay.

Given the coexistence of this multiplicity of objects, the strategic occupation of the exhibition space becomes important. This, through the installation and compositional correlation of the set of pieces in the enclosure. Therefore, the assembly becomes a means of reflection on the conditions of reception of the work, emphasizing a type of visible juxtaposition: the notable contrast between one work process and another.

Solo Show at Taller Bloc, Santiago, Chile.

JUNe 2015. Site specific, installation with tiles, Ceramic sculpture, drawings, SOPLO

Rodrigo Canala, June 2015The things that Amalia Valdés makes are, without hang-ups, happily decorative. Delightful objects.

And so what! What her work does is decorate in both senses of the word: to “adorn” (decorāre) and celebrate the places where they are exhibited, and to “recite from memory” (coro), like a visual mantra, the pattern of angles and curves that ornament them as if wanting to say something or, rather, do or show something.

The things that AV makes are, without hang-ups, happily abstract.

Objects that are concrete and, at the same time, vaporous. Heirs, perhaps, to the early abstraction of the Swedish artist Hilma af Klint, to the Swiss “mystic” Ema Kunz, to Art Deco, to pre-Columbian craftsmanship or, without going any further, to the daring although forgotten Matilde Perez 1.

Is the soul the measure of the artist?

Is the artist a measure of the soul?

Is the soul the lack of measure of the artist?

Is the artist the lack of measure of the soul?

Is the lack of measure of the soul the artist?

Is the lack of measure of the artist the soul?

Obsessively, AV’s paintings, reliefs and ceramics employ, in communion or on their own — and for some time now—, angles and curves as constructive resources. Isosceles triangles made of paper, metal, or painted on some medium and winding ropes of clay are the norm 2 and form of these constructions. The measure and/or absence of measure, a calculation and/or hesitation, constitute driving forces that broadly define her work. That said, behind this facade lies a deep conviction in making and the pleasure that this entails, or rather, in spirit or anima, understanding this term as “breath” (anima) or “vital principle” (soul).

This unnamable force is what inspires and drives the artist and what, like a poem, resides within her work.

Is the soul the measure of the artist?

Is the artist a measure of the soul?

Is the soul the lack of measure of the artist? Is the artist the lack of measure of the soul? Is the lack of measure of the soul the artist? Is the lack of measure of the artist the soul?

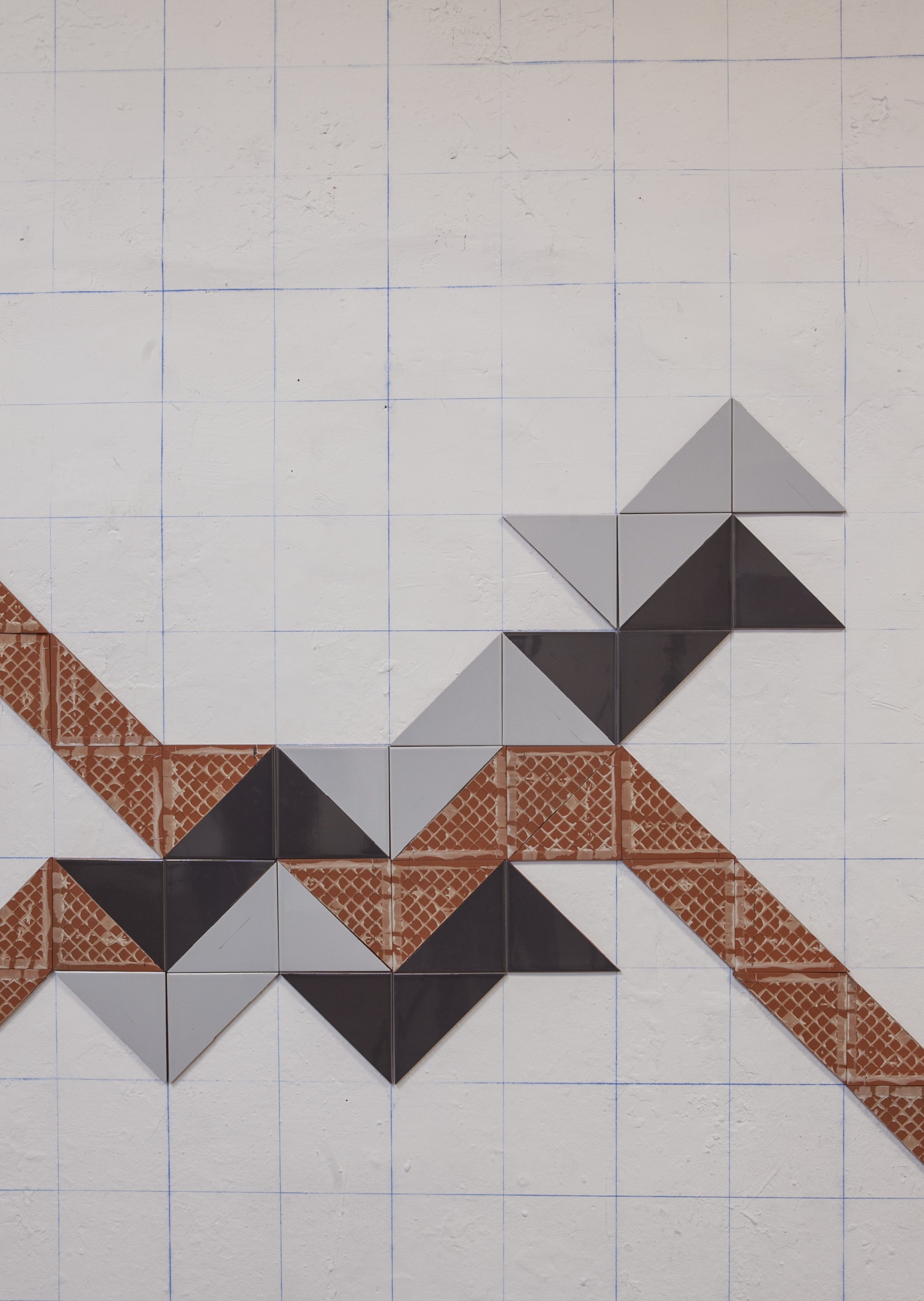

Unlike the undulating stoneware volumes, the mural installed (or rather, plastered) onto the north wall of Taller Bloc is made out of regular ceramic tiles —the ones used in bathrooms and kitchens—, just like those in some of Santiago’s subway stations. True to a stubborn work method 3, whose program is dominated by the triangle form, the artist decides to cut the 15x15 cm squares by dividing them diagonally.

Stripped of all aura and craftsmanship, and organized as modular units, the now triangular and vulgar ceramic tiles “norm and form” —after the industrial matrix that replicated them— the formless mud paste that came before. Previously, and as she often does, the artist-builder draws an enormous orthogonal grid over the ample white surface, this time with blue chalk: her map. Next, she “paints” several of what could be geometrical studies, possible chromatic combinations that, like a constellation, decorate and sparingly activate the place in all of its specificity and spatiality. Attached on both their glazed surfaces (white, gray, blue and green) as well as on their textured reverse sides (ochre and sepia), the ceramics’ arbitrary compositions do not hide, as one would expect from such a mural, the defects of the adobe wall (of a former bakery) that supports them and contains them as a frame. On the contrary, the wall actively incorporates them into the play between forms and counter-forms, exhibiting them. Craftsmanship and machinery are once again brought together. This incorporation of “faults” rejects, positively, the purely decorative premise of these works, posing a question regarding the structure and surface of things in general and of the work itself. Something similar occurs with the intervention to the studio’s staircase: the malleable and ductile paint not only adapts to the architectonic element like a shadow, it also recognizes it as its own, adding it onto itself. Step, slope and structure in general appear before the spectator as a new volume, installed there. Eyes that ascend, eyes that descend, and vice-versa.

Is the soul the measure of the artist?

Is the artist a measure of the soul?

Is the soul the lack of measure of the artist?

Is the artist the lack of measure of the soul?

Is the lack of measure of the soul the artist?

Is the lack of measure of the artist the soul?

Three years of waiting and invisibility had to pass for the convoluted mass of earthy ceramic that is exhibited today to find its base: a plinth and something else... Just like the ceramics on the contiguous wall, the artist splits in two (paints) the only two-sided surface of the regular parallelepiped, turning them into polychrome triangles. It’s frame-like condition, a characteristic of a plinth, its discreet appearance, aseptic and contained, is cosmetically altered and displaced onto an ambiguous terrain in which “base” and “object” become one, and where haptic, rectilinear, weight and breath all converge.

–

1 The failure to present her with formal recognition during her lifetime (the National Art Award) is a symptom, in Chilean visual arts, of the overvalued and badly named “political art”: an art, supposedly, with social commitment. All art that comes from an authentic artistic compromise is, necessarily, social and political. The generalized contempt towards form —from behalf of a few “advanced” thinkers— and, in particular, towards the work of M. Perez is, without a doubt and amidst so much paraphernalia-filled discourse, her main political capital.

2 Fro the latín norma: set square. Like the triangles (square triangles) present in this exhibition.

3 After being Amalia’s tutor for almost a year (she received, along with Carola Aravena, the 2014 BLOC Scholarship), I can attest to the systematic and obsessive nature of her method: work.